One issue comes up frequently in the work we do for our clients: what should someone do who doesn't want to make a tax exit, but remain a tax resident in Brazil and another country at the same time? In our experience, this dilemma is faced by whom?

- lives abroad, but keeps financial investments in Brazil;

- lives abroad and has received donations and inheritances from Brazil, or is part of succession planning;

- lives in Brazil, but is also an American citizen or has green card in the United States;

- maintain a lifestyle or profession that requires them to constantly move between Brazil and other countries (top executives, airplane pilots, "on-board" workers), not always accompanied by their families;

- lives in a border region between Brazil and another country (for example, Paraguay) and maintains a family and business in both countries.

We mentioned dual tax residency briefly when dealing with the Declaration of Final Departure from the CountryBut the subject deserves to be analyzed in more detail here.

This text will deal with the main doubts about double tax residence: (i). what it means to be a tax resident in Brazil and in another country; (ii). how the bilateral agreements entered into by Brazil to avoid double taxation of income (the "Brazilian Agreements") can be taken advantage of by the individual; and (iii). in the absence of an applicable Brazilian Agreement, how to avoid income being taxed twice. Finally, we will discuss the 3 points that should be taken into account when choosing between leaving Brazil for tax purposes or maintaining double tax residency.

What it means to be a tax resident in Brazil and in another country

Individuals who are tax residents in Brazil and in another country are in a situation of "double tax residence". This is because the legislation of each state establishes rules to determine who should be a tax resident within its jurisdiction, and each is sovereign. Brazil determines tax residency based on indications that someone intends to remain connected to Brazil, whether subjective (for Brazilians) or objective (for foreigners). The United States, on the other hand, considers everyone with American nationality to be a tax resident. Therefore, every American citizen living permanently in Brazil is a dual tax resident, even if they have never set foot in the United States.

It is extremely rare, but not impossible, for someone to have not just dual, but triple or multiple tax residency. It all depends on meeting the requirements of the tax legislation of each jurisdiction involved. From the Brazilian point of view, being a dual tax resident also means that:

- tax residence in Brazil is only lost with tax exit (whether permanent or temporary). Moving to the territory of another country, becoming a tax resident there, does not in itself eliminate tax residency in Brazil;

- the date on which a person becomes a tax resident in another country has no meaning under Brazilian law. It is possible, for example, to leave Brazil for tax purposes in one day and, before complying with the new country's tax residency rules, remain in a "limbo" in which you are not a tax resident in any jurisdiction. This situation is very rare and is usually temporary, but it is certainly possible;

- assets abroad and the income earned there must be reported in the individual income tax return (DIRPF), and the income will be subject to Brazilian taxation. This applies even if the foreign country exempts the income, or if foreign income tax has already been paid.

Almost all states now tax residents' income on a universal basis. Therefore, those with double tax residency serve two "masters"income must be taxed in the two different states, regardless of where it was earned.

It's very common for people to declare only assets and income from Brazilian sources to the IRS, while declaring the rest only to the tax authority in the foreign country. This is not only irregular but, at the extreme end, could be subject to criminal sanctions.

Is it legal to be obliged to pay tax on the same income in two different countries?

Yes. Just as each state defines who should be considered a tax resident in its jurisdiction, each state can impose its own income tax legislation. This phenomenon, "double taxation", is perfectly possible and common, to the point of being a subject negotiated in international conventions and treaties.

In most cases, however, the problem of paying the same tax twice relates to situations where an individual is tax resident in one country but earns income from a foreign source.

The most common situation of double taxation

Suppose, for example, that a consultant travels abroad a lot. During this period, he visits foreign clients, providing his services to each one for a few days. The consultant is tax resident in Brazil, but his services are performed and paid for abroad by the foreign source (the client). There is no doubt that Brazil, the consultant's state of residence, can tax the income from the provision of services. But doesn't the State of the source of the income (the country where each client is located) have the same power?

For the Source State, the consultant is taxed as a non-resident, normally with foreign tax withheld by the paying source. Brazil, as the State of Residence, may tax the income once again. The consultant then pays two taxes, one in Brazil and one abroad. In this case, the consultant has little incentive to keep clients outside Brazil, as he pays less tax when he provides the same service to a client in the country.

However, this is not interesting for Brazil's international relations. If Brazil decides to tax again, other countries could do the same in the opposite situation. There is a disincentive to international trade, and less growth in the local economy. Today, there is a certain degree of consensus that, when they act in this way, all states lose out, including Brazil.

How a state relieves double taxation

Each state is free to determine different means of alleviating or avoiding double taxation through its legislation. Traditionally, this occurs with exemptions: if Brazil stops taxing income earned abroad, it is only taxed by the foreign tax (exemption method). It is more common today, however, for Brazil, as the State of Residence, to transform the amount of foreign tax into a tax credit, offset against the amount of Brazilian tax (credit method). In this way, additional tax is only paid if the credit is less than the tax due in Brazil.

For example, suppose that in Brazil the services are taxed at a rate of 25%, and that abroad the foreign tax was 10%. In this case, tax should only be paid in Brazil on the difference of 15% (25% minus 10%). The advantage of this solution is that it equalizes the taxation of all residents in the same country: whether the consultant in our example provides services to a Brazilian or foreign client, the cost of taxation will be the same.

If, however, the foreign tax is higher than the Brazilian one (if the tax there is 30% instead of 10%, for example), the excess credits are lost, as they will only be used against other foreign source income. In this case, the consultant will still have a higher cost to serve foreign clients, but the effect of double taxation is mitigated (paying 30% is still a better solution than paying 25% in Brazil plus 30% abroad).

How to get relief

The means of obtaining this type of relief may differ according to the legislation of each state, but they are usually granted in the same way. Taking Brazil as a focus:

- identify the income by Brazilian taxation (salary, dividends, interest, etc.) - each country can classify the same income differently;

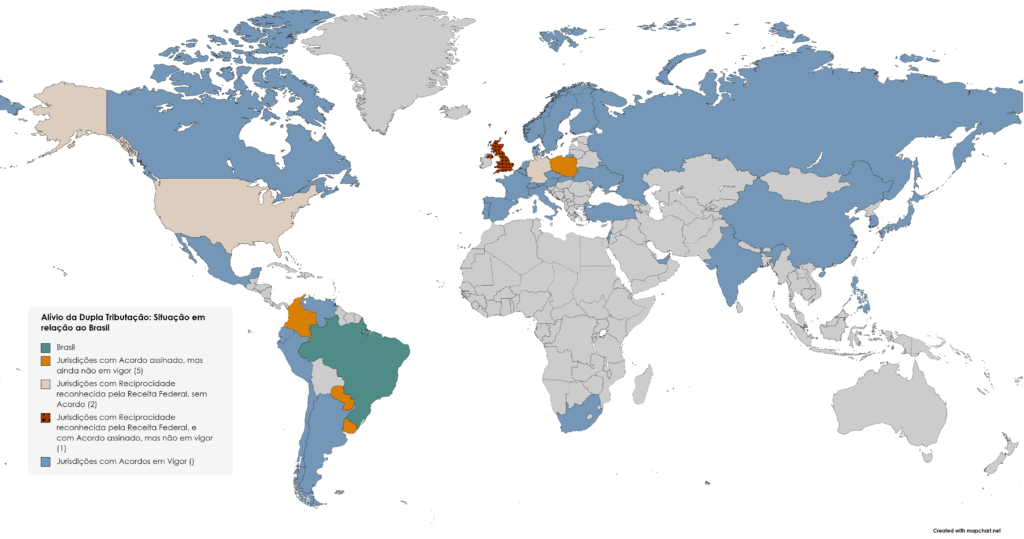

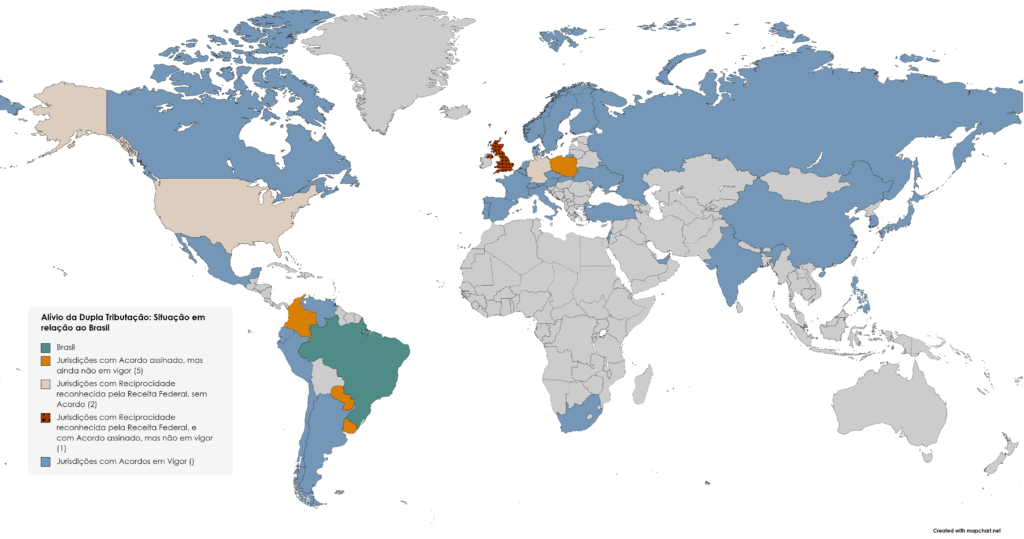

- find out if Brazil has an international agreement to avoid double taxation with the jurisdiction of the foreign country (the "Agreement")1The Federal Revenue Service maintains a updated list of Brazilian agreements to avoid double taxation. To keep track of the Brazilian agreements that are still being negotiated, or that have been signed but not ratified, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs allows you to search through the system Concordia.. The countries indicated in dark blue on the map below are those with which Brazilian agreements are currently in force;

- if there is an Agreement, identify which method the Agreement uses to avoid double taxation of that income. Generally speaking, the Agreement may provide for Brazil to exempt the income, or to grant a credit in the amount of the foreign tax. It is even possible to adopt other solutions, as long as they are expressly provided for in the Agreement;

- if there is no agreement in force, it must be verified whether domestic legislation unilaterally provides for the granting of relief. Brazil uses the so-called reciprocal treatmentBrazil allows the credit method, offsetting the amount of the foreign tax against the Brazilian tax, as long as it is proven that the domestic legislation of the other country would do the same if the situation were reversed (i.e. that the tax resident abroad would obtain the same benefit in his country if he received income from a Brazilian source).

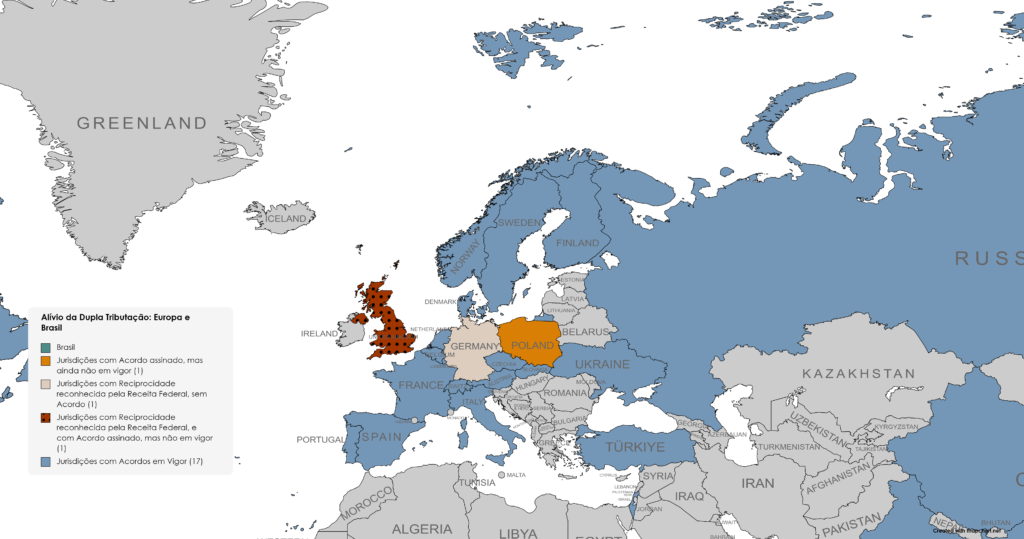

The IRS expressly waives proof of reciprocity in the case of the United States (federal income tax only), the United Kingdom and Germany, indicated on the map below in light blue. It is assumed that the legislation of these countries already grants relief, so Brazil should do the same. For the other cases, indicated in gray, the taxpayer can be asked to prove that they are entitled to credit for the amount of the foreign tax:

| Country | Situation |

|---|---|

| Argentina | Agreement in force since 1983, with changes in force since 2019 |

| Chile | Agreement in force since 2004, with amendments signed in 2022not yet ratified |

| Colombia | Agreement signed in 2022not yet ratified |

| Ecuador | Agreement in force since 1989 |

| Paraguay | Agreement signed in 2000but not yet ratified by Paraguay |

| Peru | Agreement in force since 2010 |

| Uruguay | Agreement signed and ratifiedIt should come into force in 2024 |

| Venezuela | Agreement in force since 2015 |

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The countries indicated in blue on the map are those that have already signed an agreement with Brazil. There are also those in orange that have signed an agreement, but it is still in the process of being ratified and is therefore not yet in force (Colombia, Paraguay, Poland, the United Kingdom and Uruguay). For these cases, the taxpayer needs to prove reciprocal treatment until the Agreement comes into force (except for the United Kingdom, which the IRS already recognizes).

Brazil's precaution makes sense when you consider that double taxation relief serves to facilitate international relations. It's a two-way street: if the other country isn't willing to give up part of its tax revenue to favor exchanges with Brazil, there's no incentive for Brazil to give up collecting income tax.

Again, the United States is a good example. The United States does not rely on the notion of reciprocity. Instead, they use their own criteria on what would be a foreign income tax compatible with the American one to allow offsetting of credits. As the Brazilian tax meets these criteria, the United States allows offsetting against the American federal tax. State income taxes do not allow offsetting because they follow their own legislation. For this reason, by reciprocity, Brazil understands that only US federal tax can be offset against Brazilian tax, not state income taxes.

Almost all jurisdictions around the world grant some kind of income tax relief through their domestic legislation, so it is only up to you to be able to prove this to the Brazilian tax authorities. Proof is not required before taking advantage of the credit in the income tax return itself, but only in the face of an inspection in which this point is questioned.

But what do you do if you have double tax residency?

So far, we have only dealt with the more common situation of an individual being tax resident in Brazil and earning income from a foreign source. However, we have already mentioned that double tax residence is possible and frequent. How can double taxation be avoided if both Brazil and the other country intend to tax income universally?

For countries with Brazilian double taxation agreements (dark blue on the map), there are so-called "tie-breaker rules" (tie-break rules), whereby, for the purposes of applying the Agreement, only one of the two states is considered the State of Residence. The tie-breaking rules may vary from Agreement to Agreement, but they usually stipulate that, if there is any doubt as to which of two states should be considered for the application of the Agreement, it will be the state of tax residence:

- the one where the individual keeps permanent housing;

- the one where their personal and economic relations are closest (center of vital interests), if the previous criterion fails; or

- that where to stayif the two previous criteria fail; or

- the one of which it is a nationalif the three previous criteria fail; or

- the one chosen by common agreement between the two statesif all other criteria fail.

It is worth noting that the last criterion depends on consensus between the authorities of two different states. Although there is a procedure for this, both states need to be interested in negotiating in order to resolve the issue. Therefore, what matters is to analyze on a case-by-case basis whether the main criteria are met or not. It is very rare for all of them to be exhausted without a solution.

It is important to understand the consequences of Brazil losing its position as State of Residence when applying the tie-breaker rules. Let's suppose that a Brazilian lives abroad with his family, but still intends to remain a tax resident in Brazil because he keeps certain businesses and investments here (subjective criterion). According to the tie-breaker rules, his tax residence is abroad. This person does NOT need:

- formalize the tax exit from Brazil;

- notify the sources of payment of their tax residence abroad, at least at first; nor

- failing to file a personal income tax return in Brazil.

The very application of the tie-breaker rules of an Agreement presupposes that the taxpayer maintains, under the domestic law of each jurisdiction, the situation of dual tax residence. Therefore, for all intents and purposes, the individual continues to be treated as a tax resident in Brazil under domestic law, but the application of Brazilian rules is altered to the extent provided for in the Agreement (National Tax Code, art. 98).

Suppose, for example, that an individual receives a salary from a job abroad, with no connection to Brazil. Under ordinary Brazilian tax residency rules, this income would have to be taxed at progressive rates (up to 27.5%), offsetting the amount of any tax paid abroad. The general rule of the Brazilian Agreements, however, is that income under these conditions is exempt.

In other words, even if Brazilian domestic legislation mandates taxation, the Brazilian Agreement forces Brazil to grant an exemption. In this case, in the Brazilian income tax return, this salary will need to be reported as exempt income earned abroad (rule of the Agreement), and not as income subject to the "carnê leão" system (domestic rule). Coherently, the tax paid abroad on this income is not used as a credit against Brazilian tax, since the foreign tax has been removed.

If there is no applicable Brazilian Agreement, how can double taxation be avoided for those who are in a situation of double tax residence?

For these cases, the solution of the Brazilian legislation itself applies, as already explained. All income earned abroad will be subject to Brazilian taxation, and the foreign tax can be offset if there is reciprocity of treatment by the foreign jurisdiction. The IRS automatically recognizes reciprocity in three cases: The United Kingdom, Germany and the United States (for the latter, only federal income tax). For the other cases, the taxpayer can be asked to prove reciprocity by presenting foreign legislation as proof in the event of an inspection.

If there is reciprocity of treatment, the foreign tax can be offset as a credit, taking into account the Brazilian rules for converting it into reais. Offsetting against Brazilian tax takes place up to the limit of the Brazilian tax due on foreign source income.

Likewise, if Brazilian income in the foreign state has to be subject to local taxation, the rule of that state applies to alleviate double taxation. It determines how the Brazilian tax should be used. Generally, as in Brazil, it is used as a deductible expense or as a credit against the foreign tax. At its discretion, local legislation may also prefer to exempt Brazilian income.

How to decide whether it's better to formalize your tax exit or maintain dual tax residency

In our experience, we mainly take 3 vectors into consideration when making this decision:

- Long term x short termIs the intention to leave Brazil to live abroad short term (less than 5 years) or long term (5 years or more)? If it is long-term, is it reasonable to expect this decision to be reversed, so that a return in the short term is the most likely outcome?

- Interests in BrazilEven living abroad, will there still be significant assets and income in Brazil, or will almost all income and assets be transferred abroad?

- Brazilian tax burden: in a situation of double tax residence, even with the application of an Agreement or unilateral measures to alleviate double taxation, which is more likely: that additional tax will be paid in Brazil or that nothing more will be paid?

In general, it is more interesting to maintain double tax residence, at least temporarily, if the stay abroad is short-term or has a good chance of being reversed in the short term, if the interests in Brazil remain relevant and if Brazilian taxation does not represent an additional burden. The procedures for formalizing the tax exit, mainly in terms of the exchange rate, are important, and when returning to Brazil ("tax entry") they need to be reversed. Therefore, in these cases it may be simpler and more favorable for the taxpayer to maintain dual tax residence.

On the other hand, for those who have decided to stay abroad permanently or for the long term, with no chance of reversing their decision, with no relevant interests in Brazil and under a lower tax burden than Brazil, the tax exit will be more favorable. For these cases, formalizing the tax exit is simply acknowledging a de facto situation before the Brazilian tax authorities and the sources of payment.

It is easy to see that there are situations between the two opposites mentioned, which require more detailed attention. In these terms, it is important to isolate: (i). which interests in Brazil should remain even after leaving the country, and how you intend to maintain them; (ii). which assets and income should be kept abroad, in view of Brazilian tax and exchange obligations; and (iii). whether the taxation of the foreign jurisdiction is higher or lower than that of Brazil for the relevant income items. It is the combination of this information that will enable the best solution to be identified.

On this blog you will always find relevant information and up-to-date information on the subject, as well as guiding you to avoid problems with the tax authorities and other authorities. Feel free to tell us about your experience, share the content with other friends who need guidance and contact us by e-mail at contato@tersi.adv.br or via WhatsApp. Click here to send a message now.

Check out more posts on taxation and estate planning at information for residents abroad.

Count me in!

References:

- 1The Federal Revenue Service maintains a updated list of Brazilian agreements to avoid double taxation. To keep track of the Brazilian agreements that are still being negotiated, or that have been signed but not ratified, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs allows you to search through the system Concordia.

Home › Forums › Living in Brazil and in another Country: Dual Tax Residency, Brazilian Agreements and Reciprocity